What do you think mountain towns burned by a raging wildfire, lasting 17 days and destroying 18,793 structures would look like? Close your eyes; work to imagine it.

Do you see chimneys, surviving sentinels marking the edges of homes that were incinerated? Does it look like burnt cars, the glass blown out, melted smooth around the edges due to the heat of the flame? Would you guess that the bathtubs remained stationary, and washers, dryers and fridges stood in place, marking the rooms where mothers once folded clothes, and children ran about?

Wildfire is frighteningly random, and this, known officially as the “Camp Fire,” was too; your patio furniture and china set might survive, but your brick and mortar won’t. You don’t think an appliance means anything until it is all that is left, forcing painful visions of a family’s home, once filled with laughter, and now vanished in mother nature’s (or an electric company’s) quick day of work. Eighty-five lives lost.

“Boys, this is paradise,” William Leonard, a lumber mill man, is said to have uttered in 1857 when he saw the ponderosa pines in this expansive and breathtaking Northern California vista. As you look at Paradise, California, and the mountain towns around it now, six months after the disaster, you can still conjure up the hopeful pioneers venturing west for gold, the spark plug for the 1849 Gold Rush married into the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. Now “Golden Nugget Days” becomes a community attempt to salvage some normalcy.

What is community, after all? It turns out that tangible loss can actually reinforce the invisible bonds of neighborhood.

“After you have experienced driving through a town with flames roaring through both sides of the road, you really start to question: ‘Are we really going to lose everything? Will Paradise be gone?'” says resident Kimyata Omelia, whose home burned.

“Well, we didn’t lose all of Paradise. The largest church reopened and there were 700 people there one morning. Having gone through such a traumatic event together and all the things you need to do to rebuild together, it’s something special.”

It was a tragedy, though, that no one wanted to be a part of. Her home was on a family property she’d lived on for 48 years. “I had a house and a garage and a hot tub and a stand-up tanning machine,” says Omelia. “After the fire, I was lucky if I got a hot shower or ate a warm meal. I made the mistake of not having insurance. I couldn’t afford the monthly payments and, after not making a claim for 11 years, I let my policy lapse.”

It seems as though it should be a ghost town like your grandmother’s old westerns around here, and, yet, people still wander into the Hilltop Cafe and cars hum along roads whose names are only known by the locals because the road signs melted in the heat of November 8.

Dog walkers stop to chat with a neighbor down calamitous landscapes, and businesses proudly throw up “we’re open” signs even though there aren’t many customers. People are marooned on blocks surrounded by molten ruin, living on islands of ash and twisted tangibles in homes the fire somehow skipped. Yet they are closer to neighbors than ever before in other ways, lunching with them at Paradise Alliance Church (which now draws multiple denominations and serves as a community hub) and banding together to reconstruct a new version of paradise from the ash.

It’s a disaster of such magnitude that, as with September 11, it’s known to locals by its date: November 8. During 2018, CalFire says, there were more than 7,571 wildfires that burned over 1.8 million California acres. This was the most destructive.

“November 8 presented me with unknowns I was not prepared to face. That day was a world changer and a game changer,” says Matt Plotkin, executive director of the area’s Long Term Recovery Group, which meets in nearby Chico.

However, he commended the group, which involves everyone from religious organizations to non-profits, on their hope, their sense of community, and their drive. Jim Davis, a community recovery supervisor with FEMA, added to this sentiment. He’s worked on many national disasters, including Katrina.

“I leave more hopeful. Not just the energy, but this is an absolutely remarkable community. This is one of the most remarkable trajectories,” Davis told the group. He adds: “You’re going to get tired, you’re going to get worn down. So take care of yourselves.”

There’s so much left to do. “We have absolutely zero FEMA trailers in the city of Chico right now,” says Tami Ritter, Butte County Supervisor. “As far as this being an emergency response, it’s the slowest emergency response I’ve ever seen.” However, Sheriff Kory Honea says: “FEMA has been incredibly helpful in supporting our citizens with rebuilding. Temporary housing and shelters were established early on that allowed our residents the chance to reset.”

It hasn’t been easy. “Lots of us have just struggled to figure our next move. Whether that’s in a house, or in a trailer. We were letting firefighters sleep at the station,” he acknowledges.

“I have served this community since 2000. Not just as Sheriff but in a variety of different law enforcement positions. If you look at the numbers; folks that were displaced, unaccounted for throughout the incident and deaths, this by far was the most devastating and destructive fire that this community has seen. Significant portions of our community are gone. Singed by the fire.”

Omelia sees slow improvement. “It’s getting better, but it’s been very hard. I’m a 50-year-old who was wrapping a blue tarp over my brother’s hunting trailer just to insulate myself from the cold air that takes over Paradise at night. I’ve really tried to just shuffle between the best option I could get on any given day.”

FEMA says disaster efforts start locally and then expand outward. “The debris and the housing mission have been slow, but it’s very unfortunate because…the rain, the wet, snowy weather (at higher elevations) has really impacted the recovery efforts,” said Ken Higginbotham, external affairs officer for FEMA.

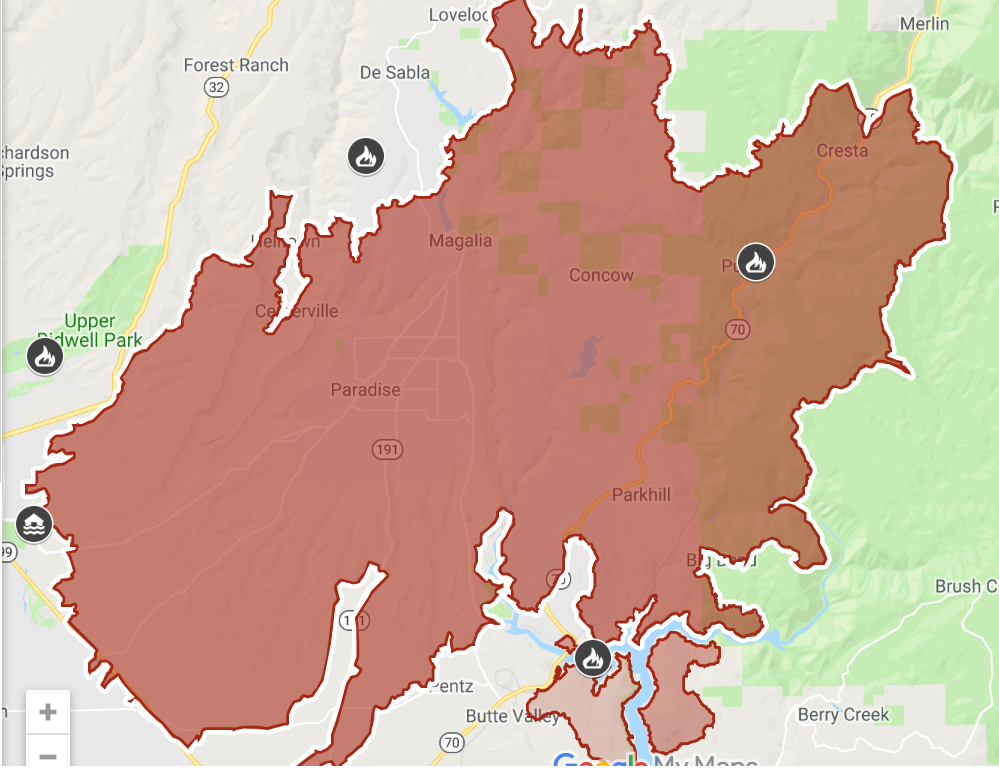

Near the famous Paradise ridge sits Magalia, a town built into the forest now made up of white RVs, plaguing the lots that once gave way to million-dollar views and, even further, Concow, an unincorporated community off Highway 70 where almost all residences burned. The people in villages like Concow and Magalia feel overlooked. Altogether, the devastation spans 240 square miles. The blaze sparked 2,000 feet up winding country roads near the Plume National Forest. Some in the national media boiled it all down to a few blocks and a single dot within a larger burn map: Paradise.

Can you blame them, though? A town called Paradise, burning.

“It’s forever affected everybody,” says Kim Dady, who waitressed in a Paradise restaurant that burned to the ground. “I’ve lost a lot of friends. A lot. It’s sad.” Yet, she and her husband are staying, in an RV turned into a home next to a melted storage shed that overlooks a grand valley near Concow. They’re building a wider defensive fire line around it. She’s started waitressing again in a restaurant in nearby Chico and some of her old regulars, but not all of them, have followed her there.

Concow and the other mountain villages are throwback hamlets embedded within the trees where hardy mountain people living off the grid still barter for goods and gather at a white-washed, one-room schoolhouse for a donated lunch brought by men from Sacramento affectionately called “The Russians” by locals. No, it’s not California suburbia; these are towns built to sustain the nature these individualistic people sought to live amongst–the tall, slim and breathtakingly beautiful oak, pine and ponderosa trees. A half million trees burned, with 91,000 fallen.

“The trees don’t realize they’re dead,” says David Stookey, who lost his home in Concow. “The sap in them boils and hardens, and water can’t travel through the tree anymore, so the tree thinks it’s alive and doesn’t fall until it essentially dehydrates.”

Remaining residents, refugees in already isolated towns, come to the metal shed at the Yankee Hill hardware store in the middle of seemingly nowhere to pick through donated clothes and shampoo samples, assisted by a man who lived in his car for weeks. With two 100-pound dogs. He fell through the cracks for governmental help because he wasn’t a homeowner and was already living on a relative’s property. He stayed for a time at the Chico fairgrounds with other Camp Fire survivors (animals stayed at the airport.) Now he’s living in a donated RV. Someone’s scattered joking handwritten Joe Dirt “honary sheriff” signs around outside.

“The news coverage kind of helped Paradise a lot,” says Rob Barber, a Concow resident. “Paradise was always on the news…No, it started here. It came over our mountains and ripped right through this place.”

Six months after the alleged spark of a PG&E electrical misfire, the Earth has begun to recover as if it is spring after a frigid winter, with budding branches, perennials sprouting, and wildflowers in areas they never were before. It looks like a storybook, even now; as a stranger to the land, it is hard to imagine what is missing, but to those who have spent their lives amongst the nature, the damage is hard to stomach, many avoiding their favorite hiking trails, unable to comprehend the vast devastation.

The Earth is beginning to forgive the damage, as it does, with the endless cycle of renewal and rebirth; the people who stuck it out remain hopeful, but many have left for good. While the land was loved, many people haven’t returned, and looters have taken kindly to this mindset, taking the last of survivors’ things, taking what little the fire has left behind. Locals say it’s too hard to get building permits; intra-governmental conflicts erupted over whether they can stay on torched plots. Adjacent Chico, which didn’t burn, has been flooded with new residents, driving up already high housing prices. “A large population of that community is embedded in the City of Chico…a city within a city,” says Chico’s Vice Mayor Alex Brown.

Humanity is put on trial in the face of great tragedy. Many people look for someone to blame, unearthing the character of all affected; some rise to be town leaders, others slink away, some take what remains, and some are just doing their best to make it through the day. It’s also a land of marijuana “grows,” open joint smoking, and motorcycle clubs. People came up here in the first place because they want nature. And freedom.

Humans are resilient, though, just like nature. Children are being educated in makeshift schools in an office complex and a hardware store or online, but the athletic teams still play. Jerry Cleek, the coach of the Paradise High School basketball team, described how, four days after the wildfire occurred, the team came together for its first practice. As he walked onto the court, he noticed the team members were high fiving one another, smiling broadly, and, most importantly, they were giving one another hugs.

The business community is equally resilient.

“With the Camp Fire, there’s just so much support; people wanting to help and support my business,” says Jamie Kalanquin, who runs a local scarf business called Thistle & Stitch. “When I was just ready to give up and be like, ‘Well, there goes everything I worked for,’ it was just the opposite.”

Drive with the windows down, and you can smell the fresh trees, the clean air. Nature bigger than man. From Chico, an artsy college town peppered with galleries and boutique shops, begin winding your way up and up and up the mountain side, through the hills and valleys toward Plumas National Forest, through Butte Valley and toward the Concow Reservoir near the Jarbo Gap. This is where it started: Pulga Road at Camp Creek Road near Jarbo Gap. The fire’s origin lies at the end of a narrow dirt passageway clinging to the side of the mountain with signs that blare “proceed at your risk” and “no pullouts.” CalFire now says the wildfire was caused by electrical transmission lines owned and operated by Pacific Gas and Electricity (PG&E). Locals talk about the “perfect storm.” High winds helped whip the fire into a frenzy they’d never seen before.

“Who knew that the trees, the thing we love most about Paradise, would become our biggest threat,” said Lauren Gill, a Long-Term Recovery Group Board Member.

Battalion Chief Curtis Lawrie was sent to Pulga that day. He was the first incident commander at the site and right away he texted his wife, saying how this fire was not like any other he has seen and that she and their children should grab the animals and get out as this danger was real. Lawrie is concerned about the health effects of breathing toxic smoke for about 36 hours without a break.

“The tinder dry vegetation and Red Flag conditions consisting of strong winds, low humidity and warm temperatures promoted this fire and caused extreme rates of spread, rapidly burning into Pulga to the east and west into Concow, Paradise, Magalia and the outskirts of east Chico,” CalFire wrote in a May 15, 2019 statement. There was also a second ignition site.

The firefighters at the Paradise Fire Station, several military men and others generational firefighters, described how bad it got. Horses and dogs freely roamed the streets, the firefighters carried cats out of houses in bags, and you can tell by their pained faces that it’s better not to ask about the people in the assisted living center where they responded to calls for help. Paradise was an aging community. Everyone pitched in, even the elderly woman in a bathrobe who helped direct traffic. People jumped out of burning cars and into rivers, and you really knew it was bad when the fire station burned. It wasn’t about putting out the fire at first, they said. It was a rescue mission. It was about saving people. And animals. And, finally, it was about trying to save things, especially the town hall, the school (which burned anyway), and other landmarks. It turned black as night outside as the fire burned. And burned.

“When you’re grabbing things to take with you, the main thought is ‘What can’t be replaced?’” says Paradise bicycle shop owner Rich Coglin. “I got up, went outside and the porch lights are on, because it’s so dark…midnight at eight a.m.”

Tracy Mohr, who works in Animal Services for the city of Chico, concurs: “The smoke was hanging over the city – and it seemed like nighttime, because the sky was so dark.”

Paradise Fire Capt. Phil Rose, whose dad was a Paradise firefighter before him, thinks wildfires are necessary for nature’s rejuvenation. They’ve existed throughout time, he says, but the destruction is greater because human beings have encroached more into the wild. The next challenge: Controlling the vegetation that is beginning to sprout up, nature replenishing itself with a fury.

“We’re just trying to do what we can to help everyone out,” says Rose. “I’ve been around this community since I was a kid. It’s hard to see the people you love go through this.”

Paradoxically, this place of natural disaster remains a spot of enormous natural beauty. Your ears may begin to pop at the altitude. The wind will whip through your hair, making you want to sing John Denver songs, and, up Skyway Road, your jaw will drop at the expansive view of rolling hills, of beautiful lookout points with waterfalls, of the place you may have imagined your whole life but didn’t know existed.

Be warned, though, that this place is not what it was. Dozens of white crosses lining the road into Paradise will remind you of this. Eighty-five lost. Rose Farrell–99-years-old. Beverly Powers–64-years-old, her emergency assistance necklace now being worn by this wooden cross on the side of Skyway Road. Victoria Taft–scrawled in a child’s penmanship across the white wood, “I love u mom.” Dorthy Mack, Teresa Ammons, Dennis Hanko, Sheila Santos, Gary Hunter, Colleen Riggs, Rafaela Andrade, Jennifer Hayes, Julian Binstock, Chris Salazar, Phyllis Salazar, Evva Holt. On and on and on, names of people, memorials of those whose lives were reclaimed by nature, by the fire that ripped through Butte County, California on November 8, 2018, leaving 153,336 acres charred, blazing for 17 days battled by 1,065 fire personnel, and forever altering the lives of thousands of Californians.

The Camp Fire stands atop CalFire’s list of the “top 20 most destructive California wildfires.” The causes of others? Human-related, power lines, electrical. A couple other fires burned more acreage but none is close when it comes to human deaths and structural damage.

Bill Stewart, co-director of The Center for Forestry at UW-Berkeley, mentioned how Paradise was on the list of towns where the worst-case scenario could become a real possibility as it is surrounded by canyons and thick forests, which is one of the many reasons that Paradise is unique. Combine that with wind, and the worst-case scenario becomes reality.

However, the deadliest wildfire in U.S. history is not the Camp Fire but one in Peshtigo, Wisconsin, where at least 1,200 people lost their lives back in 1871. The cause, according to the National Weather Service, sounds somehow similar: Human intervention. Railroad workers starting a brush fire. Today, in what could be a lesson for Paradise, Peshtigo is a healthy paper mill town of 3,000.

The recovery of Paradise, especially, has been buffeted by national support and donation.

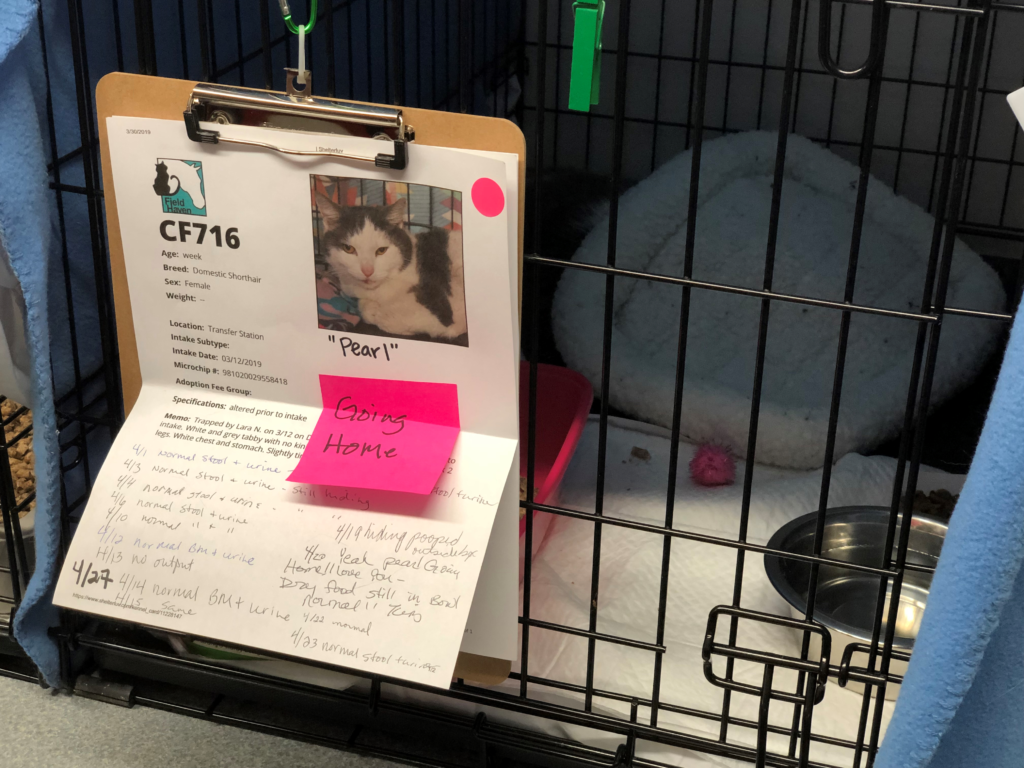

Two women from elsewhere who work for non-profit organizations are still living in an RV parked outside a warehouse in Paradise, tracking, trapping, and rescuing “fire cats” that are disbursed and still hiding throughout the area, six months out, suffering from PTSD and wounds. Many of the fire cats were pets, and their families are still looking for them. There were hundreds of such cats, and the women are still pulling them out of parched forests. Reunification between pet and owner is a way to give people who have lost almost everything tangible something back.

“…It was so big, that it was beyond anybody’s scope…ever. This was beyond Katrina,” says Joy Smith, who is the executive director at FieldHaven Feline Center, of the animal rescues following the Camp Fire.

The Paradise Inn sign remains. The neon sign visibly shouts “no vacancies,” but it’s not lit. It stands lonely on the side of the road because there is no Inn. In and out of the towns, large work trucks dominate the road, carrying everything burnt that once made up a town. A man shimmies up a burnt tree to lop off its top. The Safeway grocery store is a lunar-like landscape of shopping cart skeletons and melted ATM machines.

“Honestly, it was truly remarkable,” says resident Jerry McLean of the help that poured in. He and his wife lost everything but the clothes on their backs.

“People were driving in from Sacramento and San Francisco with food, water, clothing, just about anything that you could think of. We relied heavily upon donated toiletries early on because we literally had nothing. Many of the shelters were makeshift, obviously which caused problems when thinking of your basic living needs. Like a toilet, sink, or shower. “

At Skyway Road and Black Olive, stands the remnants of a convenience store, maybe a liquor store, though it is hard to tell. Warped metal shelves, broken glass, survived the flames. Shelves full of now emptied bottles, labels and liquor have evaporated into the Earth at the hands of the firestorm. In one plot of land, a china cabinet still stands amidst the debris. A family’s china, possibly a once cherished heirloom, remained practically intact given the circumstances.

Here and there, though, an artist’s murals are popping up like wildflowers on fire-tinged walls.

The mural wasn’t a phenomenon right away. That first mural of a young woman’s face painted in black-and-white. It’s on the only remnants of the home of an old friend: their chimney. It was through Facebook that Shane Grammer’s mural became an international sensation. It was just a piece of art he did on his friend’s burned-out home, but it turned into something much larger than he could ever imagine.

“People were so devastated in that area that it was like it was some of the first beauty they’ve seen,” says Grammer, an artist from Los Angeles who grew up in Chico.

Open your eyes. This is what paradise looks like. Locals think it will take a good 10 years to see a fuller recovery. That’s a childhood to some. It’s the rest of a lifetime to others.

How does one reconstruct Paradise? Mayor Jody Jones says she thinks Paradise will initially be smaller. “Everything will be brand new, which will be attractive and could bring more people to the community.”

Steve Bolin, executive pastor at one of the few unscathed churches, agrees. He thinks the planning and restructuring will work.

“I believe it’s going to be a great community, once we’re done.”

This story was written by University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee journalism student Madison Sepanik with reporting from Sepanik, Sal Sendik, Andrew Boldt, Dimitris Panagiotopoulos, Elizabeth Sloan, and Hailey McLaughlin.